Calling it Out: What Wimbledon Can Teach Us About AI Automation

Author Name

Zoya Yasmine

Published On

August 19, 2025

Keywords/Tags

Human-in-the-loop, Automation, Sociotechnical, Tennis

Introduction

Introduction

This year, the All England Club at Wimbledon made the decision to introduce Live Electronic Line Calling (LELC) across all eighteen match courts, replacing the human line judges that have been present on courts for nearly 150 years [1]. LELC is developed by sports technology company Hawk Eye, it uses a network of cameras powered by computer vision to track the trajectory of tennis balls in real time [1, 2]. Once triggered, the system calls “Out,” “Fault,” or “Foot fault” within a tenth of a second [1].

Yet, this technological shift dominated conversations and headlines about the tournament [3]. Notably, the poor integration of the LELC system led Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova to claim that a game was “stolen” [4] from her when the LELC was “deactivated in error” by a human operator and missed three calls in one game [5]. Furthermore, others raised concerns about the system’s error rates [3], questioning LELC’s accuracy even though the tournament organisers fiercely defended it [6]. Commentary from players has also reflected a diminished sense of agency in the face of technology that is trusted blindly [3].

Wimbledon’s decision and the debates it sparked reveal the risks of sidelining human oversight in favour of technology. This post critically examines the LELC system, highlighting the need to support “umpires-on-the-loop” by empowering them to intervene when the technology fails. It also calls for moving beyond simplistic accuracy claims about the LELC system when the design and testing conditions shape real-world performance. Additionally, it stresses the importance of engaging those impacted by the LELC (players, line callers, spectators, operations) and being cautious in how LELC are framed publicly, avoiding misleading narratives that misrepresent the capabilities of the technology to reduce human agency.

Overview of Wimbledon’s LELC system

Before this year, Wimbledon utilised the electronic line calling system in a “review” capacity [7]. Review Electronic Line Calling (RELC) meant line judges were present on the court, and players could challenge calls using the technology [7]. Arguably, one of the most fun aspects of Wimbledon was the suspense and crowd reactions from the RELC appearing on the screen after a player challenged a line judge’s call. Now, all eighteen match courts at Wimbledon use LELC exclusively, with no human line judges [1]. LELC makes real-time line calls, and players can no longer challenge its decisions since the automated call is treated as final [5]. However, they can request a replay of a particular shot for review purposes [3].

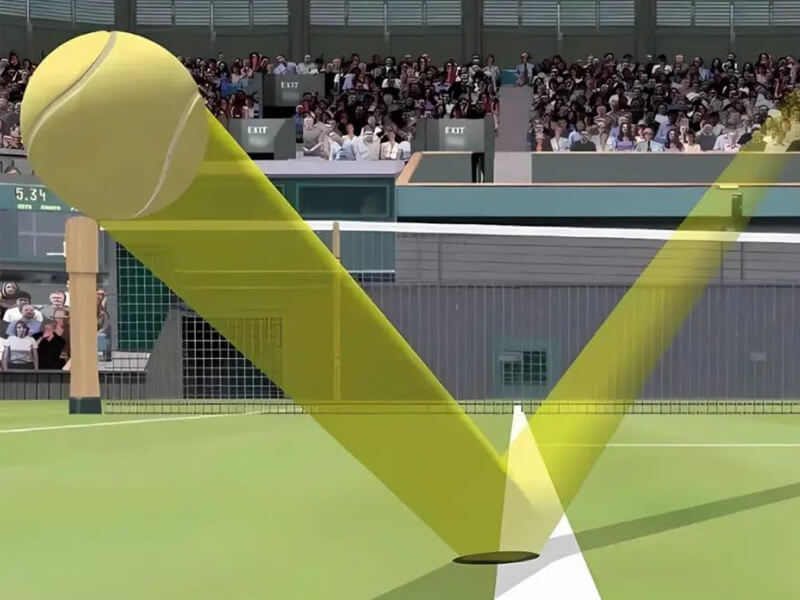

LELC uses cameras positioned around the court to track and capture the movement of tennis balls [1]. Computer vision algorithms interpret these movements in real time, creating a three-dimensional representation of the court and the ball’s trajectory [1]. This is not a video replay of the actual shot, but rather a simulation of the ball’s flight path based on its speed and trajectory [8,9]. Consequently, the final line call reflects a predicted landing spot, not the actual point of contact [8]. When the LELC detects that a ball is out or a fault has occurred, it triggers a call within a tenth of a second [1]. It is unclear what the LELC operators themselves see, but crucially for the umpire, players, and the crowd, the system only ever announces when a ball is out, but this means that a “ball in” call is visually indistinguishable from the LELC not being used at all [10].

The decision to implement LELC is not unique to Wimbledon. Other tournaments, including the Australian Open and US Open, have embraced electronic line calling in recent years [2]. However, these systems have also faced criticism [11,12,13]. In 2023, the Association of Tennis Professionals announced a tour-wide adoption of LELC starting in 2025 to “optimise accuracy and consistency across tournaments, match courts, and surfaces” [14]. This year, the Women’s Tennis Association’s Credit One Charleston Open became the first Hologic clay tournament to adopt LELC [15]. Given the reluctance to use this technology on clay, this marked a significant milestone.

Despite the increasing adoption of LELC, the French Open remains the only Grand Slam tournament that continues to use line judges and umpires to make calls as well as using ball marks on the call to determine whether shots are in or out [16,17]. In addition, at the French Open, players are not allowed to use electronic replays to challenge human decisions [17]. While the Credit One Charleston Open demonstrated that clay surfaces are no longer a technical barrier, the French Open’s stance is based on preserving tradition of human line judges and retaining human control [16,17].

The need to support “umpires-on-the-loop”

Wimbledon’s rulebook stipulates that if the LELC system fails to make a call, the chair umpire is responsible for the decision [5]. However, this protocol only applies in the absence of a call, not when an erroneous one is made. Furthermore, the rulebook states: “If the chair umpire is unable to determine if the ball was in or out, then the point shall be replayed. This protocol applies only to point-ending shots or in cases when a player stops play” [5].

This procedural structure closely mirrors what is referred to in AI literature as a “human-on-the-loop” system [18, 19]. In such systems, human oversight exists but is limited primarily to supervisory intervention in exceptional cases [18], for instance here, when the LELC abstains from making a call. The chair umpire does not continuously participate in or override routine decisions. This is a marked contrast to “human-in-the-loop” systems, where human judgment is within the AI’s decision-making loop itself, allowing for active review, correction, or override of automated outputs [19]. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the benefits of “human-in-the-loop” over “human-on-the-loop”, but the benefits of the former outweigh the latter, especially in high-context decision-making, for justification, see [18].

In her fourth-round match against Sonay Kartal, Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova was forced to replay a point after a ball that was clearly out was not registered by the LELC system (see replay of the shot in [5]). I will explore the technical causes of this failure later, but for now, it raises a concern that when AI systems make faulty or wrong decisions, humans are not being empowered to intervene and correct errors. Rather than calling the shot out, the chair umpire opted to replay the point [5]. Indeed, the umpires are not really positioned well to make these calls because from where they sit it can be hard in some cases to call shots in or out. Nevertheless, according to Pavlyuchenkova, the umpire even admitted after the match that he had seen the ball land out [4].

Had the ball been called out, Pavlyuchenkova would have won both the point and the game [4]. Instead, the point was replayed and Kartal won it to then break Pavlyuchenkova’s serve to take a 5-4 lead in games [4]. This outcome highlights a broader concern relating to the automatic deference to technological decisions, even when human judgment might offer a better alternative. While several factors can contribute to this, one commonly cited explanation is automation bias [20]. Automation bias is the tendency for humans to favour outputs from automated decision-making systems and to ignore contradictory information made without automation, even if it is correct [21].

Going further, Chiodo et al offer a deeper exploration of why human oversight may fail to safeguard against faulty AI decisions [19]. Their taxonomy recognises that points of failures largely exist in the actual human-machine interaction, such as in the process and workflow, at the human–machine interface and due to exogenous factors, as opposed to just within the AI or human components themselves [19]. As such, they argue that effective oversight is not solely a matter for “the design of the AI alone, nor just on the characteristics of the human overseer, but how they are put in relation with each other” [19, p.6].

Duarte further argues that we need to understand that “automation bias” is not inevitable and intrinsic, but the building of unwarranted trust in technology by developers through marketing tactics and manipulation [22]. In defence of the LELC, Wimbledon officials continuously reaffirmed the system’s overall accuracy relying on its unfounded claims of precision [2]. Chiodo et al’s framework underscores the need to go beyond accuracy metrics and consider whether systems are also designed in ways that enable meaningful human intervention and prevent “automation bias” [19]. Even if the technology is generally reliable, it may still fail to make calls under certain conditions, as demonstrated in Pavlyuchenkova and Kartal’s match. The problem, then, is not simply whether the AI works, but more importantly, whether the humans are structured to detect, challenge and respond to failures.

Wimbledon must critically examine and adjust its broader sociotechnical system to ensure umpires are genuinely empowered to make decisive calls, rather than defaulting to replaying points. After the match, Pavlyuchenkova expressed her disappointment with the umpire’s choice, stating, “I expected a different decision. I just thought also the chair umpire could take the initiative” [3]. Similarly, former Wimbledon champion Pat Cash described the decision as “mind-boggling,” adding, “So what if the machine didn’t say it? It was so far out and right in front of his face” [5].

Sally Bolton, CEO of Wimbledon, highlighted that “the chair umpire has primacy on court” [23] when technology fails, yet this match reveals the impossibilities exercising that authority. While it is easy to place blame on individuals for failing to intervene effectively, such a perspective risks oversimplifying the issue [19]. Instead, the focus should be on cultivating environments where umpires feel supported and confident to override automated decisions.

The need to move beyond claims of accuracy

Surprisingly, the failure of Wimbledon’s LELC system in Pavlyuchenkova’s match was not due to the inherent accuracy of the technology itself – though the accuracy has been debated and will be further discussed later. Instead, the problem arose because the LELC was manually deactivated in error by a human operator on Pavlyuchenkova’s side of the court [5]. The system remained switched off for an entire game, during which three calls on that side were missed [5]. Crucially, the chair umpire was unaware that the system had been turned off [5].

In response to the incident, Wimbledon officials ruthlessly defended the accuracy of the LELC and placed blame on “human error” for the accidental deactivation [5]. Bolton insisted: “The ball tracking technology is working effectively, was working effectively” [23] and claims about its mean error rating of 2.2mm were repeatedly cited [23, 24]. However, this defensive claim misses a critical point. Regardless of how accurate the technology is in principle; its effectiveness is non-existent if the system can be deactivated manually without warning or notification. If technology can fail so so easily, it is not a human error; it is fundamentally a design error on the part of the developers and deployers.

Moreover, we should remain cautious about these assertions of accuracy when the testing methods behind such claims are not transparent. There is no information about whether the error rating of the technology is false positive or false negative [25]. This is important because the latter could reward risky shots that target the lines, while the former could penalise this type of playing. Furthermore, it is unclear whether the tests account for real-world edge cases like wind [8], flood lights [8], lighting conditions [26], spin or slice shots [8], underarm serves [7], ball condition [27], and different court surfaces [8]? All of which have been suggested to impact the performance of LELC.

If the LELC does present systemic weak points, players may learn how it makes decisions and exploit its strengths or shortcomings, threatening the integrity of the game in the long-term [28]. By contrast, having a variety of human judges, each with their own internal methodologies, reduces the risk of such “gaming” of the system. Thus, there needs to be less focus on claims of accuracy which mask the inherent uncertainty in the technology and are often not backed up by strong evidence to support the claims.

Throughout the tournament, players voiced scepticism about the LELC’s accuracy. Emma Raducanu, after her match against Aryna Sabalenka, said she believed a call “was for sure out” despite the LELC judging the ball to have clipped the line [3]. This was not an isolated experience; Raducanu has referred to other matches where calls “have been very wrong” [3]. Belinda Bencic, though generally a fan of electronic line calling, said Wimbledon’s system “is not correct” [5], noting that even on television some calls “are clearly out or long” [5]. Jack Draper also expressed doubts about the system’s accuracy [3]. This growing doubt among players highlights concerns about the system’s real-world error rate.

This relates to broader concerns about claims of AI system accuracy and the lack of transparency regarding the testing metrics and the conditions under which human comparators are evaluated. For example, Microsoft recently claimed its AI model could correctly diagnose challenging clinical cases with over 80% accuracy, compared to only 20% accuracy by human doctors [29]. However, this benchmarking study had fundamental flaws: the human doctors were not allowed to use tools commonly available in real clinical practice and test cases were likely included in the model’s training data. Therefore, when claims that AI systems, such as the LELC, are said to outperform human judgement, we need to be more sceptical about the benchmarking, test data, and comparisons made between these two very different decision making processes.

It is important to bring to the discussion the fact that the LELC did not work for certain players and spectators. In particular, one deaf tennis fan could not enjoy Wimbledon in the same way as before because they could no longer tell whether the ball was in or out without the hand signals formally used by the line judges [30]. This reality casts the LELC’s claims of accuracy in a stark light, prompting us to ask who truly benefits from its use. It also stands as yet another example of ableist technologies introduced without normative assumptions which exclude disabled people [31], older adults [32], and children [33].

The LELC failures demonstrate why technical accuracy claims for AI systems should be critically scrutinized. Even if a system performs well in controlled tests, its practical accuracy can be undermined by design choices (such as allowing manual deactivation without alerting users) and failing to working for all users. Additionally, statistical claims of accuracy are misleading and manipulative, they should not be used to dismiss or resist challenges to the quality of AI systems.

The need to involve people impacted by the technologies

As previously noted, the LELC system faced ongoing criticism from players throughout the two weeks of the Championships. Beyond the public debate sparked by Pavlyuchenkova’s match, players such as Raducanu, Bencic, Alcaraz, Draper, and others voiced concerns about the technology’s reliability: “we players talk about it and I think most of us have the same opinion” [3]. Some even went as far as taking photos of marks on the court to support their claims [8].

While criticisms have been particularly vocal at Wimbledon, these issues are not unique to this tournament. For instance, at the 2024 Cincinnati Open, Nakashima hit a forehand clearly out during his match against Fritz, but the LELC failed to trigger an out response [34]. At the 2024 Miami Open, Carlos Alcaraz expressed frustration about some of the calls made by the LELC system [35]. These incidents highlight a troubling pattern whereby technology is rolled out in the name of accuracy and efficiency, but when those closest to and most impacted by it such as players voice concerns, their feedback is often dismissed and they’re actively being told not to believe their own eyes [35].

The Horizon IT Post Office injustice vividly illustrates this point. Sub-postmasters repeatedly reported problems with the new Fujitsu Horizon IT software which caused unexplained balancing errors [36]. As a result, many sub-postmasters were forced to cover these shortfalls from their own pockets to avoid breaching their contracts with the Post Office [36]. Despite these reports, the Post Office steadfastly insisted that Horizon was robust and failed to disclose its knowledge of “bugs, errors, and defects” within the software [37].

When human line judges were still part of the game, players had the option to challenge calls made by officials using the RELC technology. However, with the introduction of the LELC system, players no longer have the ability to challenge decisions, and umpires can only intervene if the system fails to make a call [5]. Although screens display replays of close calls, these cannot be overruled, and there is no formal avenue for redress. As technology becomes increasingly integrated into decision-making processes that affect people’s careers and livelihoods, the ability for users to question and challenge decisions is eroding. Paradoxically, this is precisely the moment when listening to and incorporating the perspectives of those impacted should be prioritised more than ever [38].

When individuals raise concerns about technology and those concerns are dismissed without meaningful attention or investigation, trust inevitably erodes. This loss of trust was clearly evident among many Wimbledon players regarding the LELC system [3]. When asked if she trusted the technology, Emma Raducanu responded, “No, I don’t – I think the other players would say the same thing, there were some pretty dodgy ones but what can you do?” [3]. But what is most alarming is not just the lack of trust itself, but the lack of agency players feel in the face of a system they do not trust. Iga Swiatek echoed this sentiment, expressing doubts about the LELC yet saying she “has to trust them” [4].

The narratives of the inevitability of the flawed LELC being used at Wimbledon is deeply concerning [39]. Despite widespread doubts about the accuracy of such technologies, players felt powerless to influence or challenge how these systems are integrated into processes that fundamentally affected their lives. Claims of technological accuracy create an environment where people’s ability to make decisions or raise objections is diminished. While the Horizon IT scandal led to hundreds of wrongful criminal convictions, Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova also felt a sense of injustice after her match stating simply in reference to the LELC system: “they stole the game from me” [4].

Strange argues that relying on vague claims like “our product is trusted!” because this. treats trust as a one-way process. In these instances, AI developers are simply tasked with convincing users about the safety and efficacy of their systems, instead of earning that trust with users [40]. Instead, Strange suggests that trust should be reframed as a dynamic negotiation which involves a continuous process embedded within the development and implementation of AI [40]. Trust is not merely about achieving an outcome or a statistic of accuracy. This does not equate to legitimacy as people want decisions that are not only correct, but also respectful, transparent, and fair [9,41].

Wimbledon and the developers of the LELC need to continuously engage with players and also spectators to understand the flaws of the technology and whether it truly addresses the issues it was intended to address [see pillar 1 in 38]. While human line callers may have made mistakes, they were relatively fewer issues. As Rothenburg points out an interesting comparison, it’s hard to imagine the equivalent of four or five human officials suddenly going unconscious simultaneously at a crucial point [10]. Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova has advocated for greater agency in the LELC decision-making process, suggesting tennis adopt video review systems like football, allowing players to challenge calls [6]. Draper claimed that it was a “shame” that human line judges were removed from the tournament [42].

Beyond the pursuit of accuracy and efficiency, players and spectators have highlighted that human line judges were a cherished part of Wimbledon’s history and tradition [41, 43]. While values like emotion, tradition, and theatre are harder to measure and quantify like accuracy, Li argues that sport thrives on these elements [41]. For just under 150 years, line judges were integral to Wimbledon’s identity, and such a profound change should have involved greater consultation with those impacted.

While other tournaments have adopted LELC technology, often amid controversy, it is unclear what consultation and with whom Wimbledon undertook before implementing the system. The lack of transparency surrounding the decision undermines the legitimacy of the technology and erodes trust. This makes technological deployment seem inevitable and beyond human control, when it is not: the French Open (Roland Garros) is a good example of this. On the decision not to use the technology, the French Tennis President explains: “at Roland Garros we want to keep our linesmen as long as the players agree with that. If sometime the players say we don’t want it then maybe we will have to change” [16].

The need to be careful about how technology is framed

On a final note, it is important to more explicitly discuss how the LELC was framed. As Professor Li points out, the adoption of this new technology was presented as a step toward greater accuracy and consistency [41]. However, it was likely also motivated by a desire to “cut costs, speed up matches, and reduce reliance on human labour” [41]. This distinction matters because we are increasingly seeing technologies deployed under the guise of user benefits, while in reality they serve corporate interests by cutting corners and maximizing profits. Where the analysis earlier undermined claims about the accuracy of the technology, there is a need to question the claims and reasons for the introduction of the LELC system and ask whose interests they truly serve.

The notion of reducing human labour is also worth unpacking. While there are frequent claims that “AI is taking our jobs,” a paradox often goes unacknowledged: AI systems are frequently portrayed as fully autonomous, when in reality they depend heavily on human labour and use little “AI” technology (also referred to as AI washing) [44]. In the case of Wimbledon’s LELC, although the technology replaced human line judges, about 80 former line judges were retained on court as assistants, albeit without decision-making authority [3]. Additionally, the system is monitored by a team of roughly 50 operators and review officials tasked with ensuring the technology functions properly [1]. Crucially, the LELC depends on human operators to perform essential tasks such as selecting the correct service box and initiating tracking before each serve [1], underscoring how “automation” often remains deeply intertwined with human labour.

Behind many supposedly seamless and efficient AI systems, there are still numerous humans performing manual work to keep them running smoothly. A well-known example is Amazon’s “Just Walk Out” stores, which claimed to offer a cashier-free shopping experience [45]. In reality, thousands of workers were monitoring store cameras and labelling shopper footage to support the system [46]. While this post does not suggest that Wimbledon’s LELC involves the same issue, the example illustrates that deploying technology to reduce human labour is far more complex than it appears. This further calls into question the purported benefits of such technological innovations.

In addition, media coverage often described the LELC as an “AI line judge” [24, 30]. While this may sound harmless, equating the technology with a human line judge is misleading because they function in fundamentally different ways. Unlike human judges, the LELC’s decisions are based on computer simulations rather than direct footage which is a critical distinction [8]. Such framing risks inflating public expectations and obscures the reality of the technology’s limitations, as such people believe that the LELC shows “fact in graphic form” [9].

The LELC was also often described as a “robot,” a misleading term that conflates artificial intelligence with robotics which are two fundamentally different technologies. This kind of mislabelling can fuel unnecessary fears about AI “taking over” or replacing humans distracting from the more accurate and complex reality whereby these systems rely heavily on ongoing human oversight, intervention, and collaboration behind the scenes [47].

Conclusion

The implementation of the LELC system at Wimbledon highlights the complex challenges that arise when integrating automated technologies into high-stakes decision-making environments. While the technology promises greater accuracy and efficiency, this paper has shown that accuracy alone is insufficient to guarantee fairness, legitimacy, or trust. “Human-on-the-loop” umpires need adequate support, empowerment, and ability to exercise discretion when the LELC fails. The author calls for more meaningful engagement with players, operators, line judges, and spectators about their views on how the LELC should be implemented at Wimbledon. Furthermore, we need to shift away from prevailing narrative framing the LELC as an infallible “AI line judge” to prevent unrealistic expectations of the technology. Call it what it is: a ball predicator with all its limitations, benefits, and this will provide us with a more meaningful foundation to actually determine whether this technology is beneficial at all, and how it might be used if so.

The author would like to thank everyone whose work and conversations inspired this blog post. In particular, thank you to Maurice Chiodo and Jean-Luc Wetherall for their detailed comments on the draft as well as the work of the Ethics in Mathematics Project and We and AI that hugely influenced by thinking on this topic.

Image credit: sourced from Openverse, “Line up” by #96 is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Remixed using techniques from the Archival Images of AI Playbook.

References

- [1] Wimbledon. The Precision Operation: Introducing Electronic Line Calling [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.wimbledon.com/en_GB/news/articles/2025-07-03/the_precision_operation_introducing_electronic_line_calling.html

- [2] Dixon, E. Wimbledon apologises after electronic line-calling tech failure [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.sportspro.com/news/wimbledon-electronic-line-calling-tech-failure-error-hawk-eye-july-2025/

- [3] Hogwood, C. Wimbledon: Why electronic line-calling is causing controversy as Emma Raducanu and Jack Draper question system [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.skysports.com/tennis/news/32498/13393602/wimbledon-why-electronic-line-calling-is-causing-controversy-as-emma-raducanu-and-jack-draper-question-system

- [4] Oxley, S. ‘They stole the game’ – electronic line call fails at Wimbledon’ [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/tennis/articles/cz9k1071kp3o

- [5] Scott, L. Oxley, S. ‘Human error’ – Wimbledon sorry over missed line calls’ [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/tennis/articles/czry1j5e32ko

- [6] Scott, L. Wimbledon announces change after line call controversy [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/tennis/articles/c3vd1w9kr3lo

- [7] LTA. Working with Electronic Line Calling [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.lta.org.uk/494ef6/siteassets/lta-officials/my-resources/role-specific-resources/working-with-electronic-line-calling.pdf

- [8] Knapton, S. The science that shows Hawk-Eye isn’t as accurate as it seems [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2025/07/12/the-science-shows-hawk-eye-isnt-accurate-seems/

- [9] Collins, H. Evans, R. You cannot be serious! Public understanding of technology with special reference to “Hawk-Eye”. Public Understanding of Science [Internet]. 2008 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0963662508093370

- [10] Thank you to Maurice Chiodo for pointing this idea out more clearly. Also mentioned in: Rothenberg, B. Calling Out for Humanity in Tennis [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.benrothenberg.com/p/wimbledon-2025-line-judge-hawkeye-failure-electronic-line-calling-failure-centre-court-anastasia-pavlyuchenkova-calling-out-for-humanity-in-tennis

- [11] Syed, Y. Naomi Osaka confronts Australian Open umpire in awkward hawkeye showdown [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.express.co.uk/sport/tennis/1999745/Naomi-Osaka-Australian-Open-umpire-hawkeye

- [12] TNT Sports. Australian Open 2023: That is strange! – Bizarre decision from electronic system stuns umpire and players [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.tntsports.co.uk/tennis/australian-open/2023/australian-open-2023-that-is-strange-bizarre-decision-from-electronic-system-stuns-umpire-and-player_sto9350748/story.shtml

- [13] France, S. US Open tournament director says whether she’s worried about automated line calling after Taylor Fritz incident [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.thetennisgazette.com/news/us-open-tournament-director-says-whether-shes-worried-about-automated-line-calling-after-taylor-fritz-incident/

- [14] ATP Tour. Electronic Line Calling Live To Be Adopted Across the ATP Tour [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: http://www.atptour.com/en/news/electronic-line-calling-release-april-2023

- [15] WTA Tour. Credit One Charleston Open becomes first clay tournament to use ELC Live [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.wtatennis.com/news/4239258/credit-one-charleston-open-becomes-first-clay-tournament-to-use-elc-live#:~:text=Credit%20One%20Charleston%20Open%20becomes%20first%20clay%20tournament%20to%20use%20ELC%20Live,-1m%20read%2026&text=The%20Credit%20One%20Charleston%20Open,March%2029%20to%20April%206.

- [16] WTA Tour. Still seeing it, still calling: Roland Garros preserves the art of the human line call [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.wtatennis.com/news/4278359/still-seeing-it-still-calling-it-roland-garros-preserves-the-art-of-the-human-line-call

- [17] Chowdury, T. Why does French Open not have electronic line calling? [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/tennis/articles/clygxnkddg9o

- [18] Nothwang, W. Burden, R. McCourt, M. Curtis, W. The Human Should be Part of the Control Loop? [Internet]. 2016 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://faculty.washington.edu/sburden/_papers/NothwangRobinson2016resil.pdf

- [19] Chiodo, M. Müller, D. Siewert, P. Wetherall, J. Yasmine, Z. Burden, J. Formalising Human-in-the-Loop: Computational Reductions, Failure Modes, and Legal-Moral Responsibility [pre-print]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2505.10426

- [20] Mosier, K. Skitka, L. Heers, S. Burdick, M. Automation bias: decision making and performance in high-tech cockpits [Internet]. International Journal of Aviation Psychology. 1997 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11540946/

- [21] Alon-Barkat, S. Busuioc, M. Human-AI Interactions in Public Sector Decision Making: “Automation Bias” and “Selective Adherence” to Algorithmic Advice [Internet]. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2023 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article/33/1/153/6524536

- [22] Duarte, T. The human cost of automation bias [Internet]. 2024 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://weandai.org/the-human-cost-of-automation-bias/

- [23] McLeman, N. Wimbledon chief pits neck on line after being left in dark over centre Court mishap [Internet]. 2025 [cited on 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.express.co.uk/sport/tennis/2078495/wimbledon-centre-court-sally-bolton

- [24] Patrick, P. In defence of Wimbledon’s AI line judge [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/in-defence-of-wimbledons-ai-line-judge/

- [25] Thank you to Maurice Chiodo for drawing attention to this point.

- [26] Addicott, A. Ben Shelton Talks Hawk-Eye After Completing Suspended Wimbledon Match With One-Minute Service Game [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.ubitennis.net/2025/07/ben-shelton-talks-hawk-eye-after-completing-suspended-wimbledon-match-with-one-minute-service-game/

- [27] Choppin, S. Albrecht, S. Spurr, J. Chapel-Davies, J. The effect of Ball Wear on Ball Aerodynamics: An Investigation Using Hawk-Eye Data [Internet]. 2018 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2504-3900/2/6/265

- [28] Thank you to Maurice Chiodo for drawing attention to this point.

- [29] Nori, H. et al. Sequential Diagnosis with Language Models [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/html/2506.22405v1

- [30] Briggs, S. Wimbledon slaps down Raducanu and Draper over AI line judge row [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/tennis/2025/07/05/wimbledon-slap-down-raducanu-and-draper-ai-line-judge-row/

- [31] Alan Foley and Fasika Melese. Disabling AI: power, exclusion, and disability [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. British Journal of Sociology of Education. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01425692.2025.2519482?src=

- [32] Chu, C et al. Digital Ageism: Challenges and Opportunities in Artificial Intelligence for Older Adults [Internet]. The Gerontologist. 2022 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/gerontologist/article/62/7/947/6511948?login=false

- [33] Mahomed, S. Aitken, M. Atabey, A. Wong, J. Briggs, M. AI, Children’s Rights & Wellbeing: Transnational Frameworks [Internet]. 2023 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.turing.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2023-12/ai-childrens_rights-_wellbeing-transnational_frameworks_report.pdf

- [34] Eccleshare, C. Taylor Fritz’s Cincinnati electronic line calling dispute shows need for tennis common sense [Internet]. 2024 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/5700156/2024/08/14/taylor-fritz-cincinnati-electronic-line-calling-umpire-allensworth/

- [35] Eccleshare, C. Tennis adopted electronic line calling on clay and created a ball-mark monster [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/6320584/2025/04/30/tennis-electronic-line-calling-clay-ball-marks-umpires/

- [36] Flinders, K. Post Office Horizon scandal explained: Everything you need to know [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.computerweekly.com/feature/Post-Office-Horizon-scandal-explained-everything-you-need-to-know

- [37] Espiner, T. Carr, E. Post Office scandal had ‘disastrous impact on victims’ [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cz9k4lvg77lo

- [38] Chiodo, M. Müller, D. Manifesto for the Responsible Development of Mathematical Works: A Tool for Practitioners and for Management [Internet]. 2023 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2306.09131

- [39] Eccleshare, C. Wimbledon line judges being replaced was ‘inevitable’ says All England Lawn Tennis Club [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/athletic/6421206/2025/06/12/wimbledon-line-judges-replaced-electronic-line-calling/

- [40] Strange, M. Beyond ‘Our product is trusted!’ – A processual approach to trust in AI healthcare [Internet]. 2024 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-3825/paper2-1.pdf

- [41] Li, F. Wimbledon’s electronic line-calling system shows we still can’t replace human judgement [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.bayes.citystgeorges.ac.uk/news-and-events/news/2025/july/you-still-cannot-be-serious

- [42] Sinmaz, E. Wimbledon chiefs defend AI use as Jack Draper says line calls not ‘100% accurate’ [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2025/jul/04/wimbledon-chiefs-defend-ai-jack-draper-line-calls-not-100-accurate

- [43] Hincks, M. I’ve sat through 130 matches at Wimbledon and they’ve ruined the fan experience [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.msn.com/en-gb/sport/tennis/i-ve-sat-through-130-matches-at-wimbledon-and-they-ve-ruined-the-fan-experience/ar-AA1I64PX

- [44] Woollacott, E. What is ‘AI washing’ and why is it a problem? [Internet]. 2024 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c9xx8122893o

- [45] Brindle, J. So, Amazon’s AI-powered cashier-free shops use a lot of… humans. Here’s why that shouldn’t surprise you [Internet]. 2024 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/apr/10/amazon-ai-cashier-less-shops-humans-technology

- [46] MacInnes, P. Farewell tradition, hello robots: Wimbledon adjusts to life without line judges [Internet]. 2025 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2025/jun/30/farewell-tradition-hello-robots-wimbledon-adjusts-to-life-without-line-judges

- [47] Dilal, K. Duarte, T. Better Images of AI: A Guide for Users and Creators [Internet]. 2023 [cited 09 August 2025]. Available from: https://blog.betterimagesofai.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Better-Images-of-AI-Guide-Feb-23.pdf