Why We Need Better Images of AI From Science Fiction

Author Name

Yeliz Figen Döker and Zoya Yasmine

Published On

July 24, 2025

Keywords/Tags

Science Fiction, AI Visuals, AI Narratives, AI Imaginaries

Science fiction plays a decisive role in shaping perceptions of technology, particularly artificial intelligence (AI), not only through its literary narratives but even more pervasively through its audio-visual representations. These depictions do not merely reflect technological developments; they actively influence how we perceive and relate to emerging technologies long before they enter our daily lives. Through imaginative storytelling and the development of ‘diegetic prototypes’ (1), science fiction also inspires ideas about what the future of society should and shouldn’t look like.

However, when we look at science fiction from a more critical perspective, it becomes clear that there is a divide between the literary version of science fiction (s.f.) and its adaptation in motion pictures (eye-sci-fi) (2). Therefore, in this blog post, we examine the limitations of common AI images drawn from eye-sci-fi and introduce Better Images of AI (3), a free library that provides alternative images that offer more representative and inclusive visuals of AI. By highlighting these issues, we hope to encourage others to rethink how AI is represented and to develop new, more inclusive images of AI that carry the ethos of s.f.

“Science fiction does not just offer speculative representations of social reality it may, in various ways, help to shape it” (Brennan, 2016) (4)

Science fiction as a causative force

Science fiction is a genre that explores the unlimited possibilities of imagination while also basing it on the tangible realities of scientific discovery. This very harmonisation, blending factual elements with imaginative concepts, makes it the prime example of an oxymoron (5). As such, the rise of science fiction can be viewed as a natural reaction to the rapid pace of scientific advancements.

In addition, science fiction helps shape the future by preparing the minds of scientists and laypersons. Indeed, in the 1960s, computer scientists at MIT popularised certain narratives in film and journalism to influence the direction of future research and the greater adoption of their lab’s computing technologies (6). Also, the launch of the first Russian Sputnik marked the beginning of the space race that defined the 20th century. In fact, it is no coincidence that Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, known as the father of space flight and the founder of astronautics and rocket science, was also a science fiction author (7). Not to mention that the great astronomer Edwin Hubble was inspired by the works of Jules Verne, often regarded as one of the founding figures of the genre. This motivation to enter scientific fields often springs from the deep admiration and passion that scientists feel for science fiction. These illustrate that it does not solely predict the future; it also helps devise it. Its influence extends beyond imagination and speculation, shaping the aspirations of those who invent new technologies, make scientific advancements, and strive to make the impossible possible.

The limits of “eye-sci-fi” and the value of “science fiction”

However, audio-visual representations of science fiction often fail to capture the depth and critical edge of its literary form. Instead, they tend to fall back on familiar, anxiety- and action-driven tropes with the help of extensive usage of visual effects, like killer robots (8), godlike AIs, and dystopian collapse, which in turn dominate the visual language of science fiction. This flattening effect reinforces outdated and misleading ideas about technology, sidelining the experimental and diverse visions found in the works of authors like Robert Heinlein, Brian Aldiss, Stanislav Lem, Philip K. Dick, Alice Sheldon (James Tiptree, Jr), or Octavia Butler.

According to Isaac Asimov, one of the most prolific authors of science fiction, this divide traces back to the very abbreviations used to categorise the genre (9). In his reflections on science fiction, he describes it as split between printed science fiction (s.f.) and motion-picture science fiction (eye-sci-fi) (9). He points out that “good” science fiction must necessarily have a high intellectual content, because it must deal with science and people and their interactions in a reasonable and knowledgeable manner (9). However, eye-sci-fi often fails to meet these criteria; instead, it focuses on visual special effects, including spectacles of vast destruction, alien or monstrous beings, and feats made possible by zero gravity or wild talents. In his view, eye-sci-fi tends to prioritise special effects, with each production aiming to surpass its predecessors in spectacle to secure commercial success. He maintained that this reliance on spectacle makes eye-sci-fi almost a different genre altogether. With the boom effect provided by Hollywood, eye-sci-fi quickly achieved enormous popularity, generated unprecedented profits, and inspired a wave of imitations. Yet, Asimov believes that these imitations rarely matched the quality of the original works in science fiction. His critique remains relevant, as seen in many contemporary adaptations. Just recently, Netflix’s adaptation of Cixin Liu’s The Three-Body Problem was widely described as flat and shallow compared to its original (10), with some arguing it was produced by and for Western audiences as opposed to its more diverse origins (11).

The problems with relying on eye-sci for AI imagery

“Narratives of intelligent machines matter because they form the backdrop against which AI systems are being developed, and against which these developments are interpreted and assessed” (Cave, Dihal and Dilon, 2020) (12)

Eye-sci-fi images are just not that imaginative

While the s.f. can push us to think about the future in novel and original ways, eye-sci-fi often falls back on well-worn narratives that restrict us from imagining technology unconstrained from existing power structures. The dominant stock images of AI are an extension of this myopic perception. Recurring stereotypes, overly sexualised gynoids reminiscent of Hel in Metropolis, rogue killer cyborgs from Terminator, or white-skinned, blue-eyed robots with glowing positronic brains as depicted in the I, Robot film, are typically based on the metaphors drawn from a simplified interpretation of eye-sci-fi.

In relation to how these eye-sci-fi visuals influence our thinking about AI, we argue that they create illusions of inevitability, reinforce harmful representations of race and gender, and divert attention from the real AI developments that are happening right now, such as biased algorithms, mass surveillance, environmental damage, and worker exploitation.

Eye-sci-fi has a diversity problem

One of the most troubling aspects of eye-sci-fi-inspired AI images is their lack of diversity. A study by Cave et al of 142 influential AI-themed films from 1920-2020 found that only 9 AI professionals depicted were women (13). Eye-sci-fi narratives have a tendency to misrepresent the history of AI, which has benefited from the works of diverse communities – for instance, black researchers at MIT working at Project MAX (6), a computation-focused research group or the many women at Bletchley Park (6) behind the success of Alan Turing’s Enigma machine. Despite this, images of AI often overlook and misrepresent the real lives of women, people of colour, disabled individuals and other marginalised groups.

Beyond the representations of those working in the AI industry, Law (6) comments on the visions of the future often portrayed in science fiction cinema. This is not only in terms of who appears on screen, but also in the kinds of futures these works imagine. The aesthetics, values, and power structures they normalise tend to follow familiar, exclusionary patterns. This lack of diversity is not solely about representation, but about the imaginative limits placed on what futures are thinkable and advocated for.

For instance, the 1927 film Metropolis (14) features a robot turning into a white woman, a transformation maliciously orchestrated by a white-male-mad scientist who abducts “Maria” and imposes her likeness onto the machine, “Hel.” Furthermore, in this case, the robot is modelled on Maria, a saintly, Madonna-like figure, yet it later becomes her opposite, a hypersexualised, deceptive, and destructive version. What is troubling is not only the racial coding of the machine but also the rigid moral division it constructs. The ‘good’ woman is human, submissive, and pure, whereas the ‘bad’ woman is artificial, desiring, and dangerous. Rather than offering a critique of automation or identity, the film ultimately mirrors long-standing cultural anxieties about women who do not conform. We also note that science fiction scenes involving ‘human-machine-symbiosis’ often reinforce the idea that the futures of computing are inseparable from notions of whiteness. In doing so, eye-sci-fi promotes the idea that AI technologies are built by/for white individuals or certain gender prototypes, overlooking the role of minoritised groups played in the development of AI. These biases influence not only who is viewed as an AI developer but they also skew our perception about who should be included in conversations about its governance and development.

Eye-sci-fi tropes exaggerate AI’s capabilities and create fearmongering

Eye-sci-fi often portrays AI as vastly more powerful than it actually is. These misleading images can exaggerate the possibilities or scope of what the technology is capable of, which creates a disconnect between reality and how it is viewed by the public. The use of inaccurate images can be intimidating to people who are non-experts, as the visuals construct a future that can appear dystopian, disturbing, and create a culture of distrust or worry about AI. While such exaggeration might seem inherent to the genre’s speculative nature, as its role is to ask “what-ifs”, these portrayals do not emerge in a vacuum. They are closely entangled with the conceptual development of AI itself.

Since the theoretical foundations (15) of the field were laid by Alan Turing and its formal naming at the Dartmouth Workshop in 1956 (16), many have argued that the ultimate aim of AI has been the creation of human-level, or even general intelligence that surpasses human-level. This ambition has led to a taxonomy within the field that distinguishes between Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI), Artificial General Intelligence (AGI), and Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) (17). While ANI refers to systems that perform specific tasks, such as image recognition or language translation, AGI denotes a still-hypothetical system that is expected to perform generality in many domains and be capable of flexible, human-like reasoning across domains (18). ASI, in contrast, refers to intelligence that would surpass human capabilities altogether, which also simply does not exist at the moment.

Science fiction can indeed serve as a powerful tool for critical reflection and learning. However, the dominant tropes of eye-sci-fi often obscure rather than clarify the real challenges posed by the AI that we interact with today. Stock imagery depicting AI often exaggerates the reality, desirability, and even existence of AGI and ASI. Although it is natural for the genre to imagine beyond present capabilities, it is important to question which visions gain prominence and why. Many literary works do offer more complex and less anthropocentric visions of machine intelligence, but these are too often eclipsed by blockbuster simplifications. Thus, we advocate for deeper engagement with literary portrayals of AI that resist these tropes, particularly those that do not hinge on the assumption that AI will inevitably dominate humanity or that its future capabilities must be framed through the lens of “superhuman intelligence.”

What are some of the limiting eye-sci-fi images and their impact on the perception of AI?

The persistent use of misleading AI visuals can lead to inflated expectations, which obscure the real and present challenges that AI poses.

Some of the most common eye-sci-fi AI images include (19):

- Descending code:popularised by The Matrix, these visuals refer to a dystopian science fiction scenario in which humans are enslaved by AI. To those for whom the link to the Matrix films is not clear, images of descending code can be alienating by presenting AI as a wall of incomprehensible symbols.

- The human brain: Although only a portion of AI research attempts to reconstruct the human brain electronically, the digital version of the human brain is generally used when describing the functions of AI. Treating the human and AI brain structures as equal gives the impression that AI must mimic the human brain.

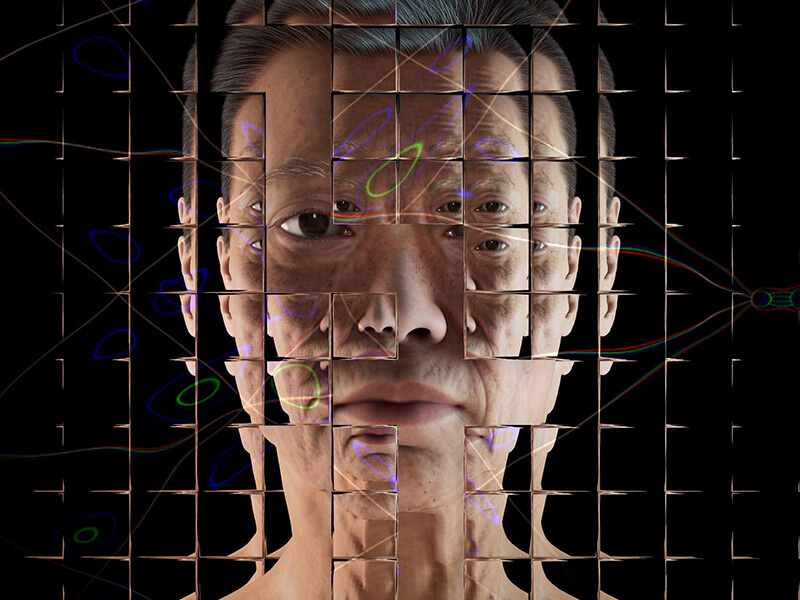

- White robots:the embodiment of AI as robots that are white in colour, ethnicity or both, associates intelligence with being white. Such images serve as a barrier to increasing racial and ethnic diversity in AI development and decision-making, and exclude the global majority.

Breaking free from common tropes in eye-sci-fi with science fiction

“Futures can warn and promote, and hold the power to exclude as well as include.” (Law, 2024) (6)

Images from eye-sci-fi are limited by the fact that they are usually derived from audio-visual depictions and adaptations of science fiction. Eye-sci-fi mediums need to attract large, diverse audiences, so it is understandable that they do this through identification with characters using universal human traits and also sensationalist narratives (4). While these formats are effective at engaging viewers, they often constrain the way we explore and think about AI by only representing it in terms of its similarity to humanity and its inevitability to take over the world. This framing makes it harder to see AI for what it is and the more diverse imaginings of what it could become.

The eye-sci-fi images of AI severely lack any positive images which show humans having agency and being in control of the technology, as opposed to being threatened or marginalised by it. Indeed, Noessel’s ‘Untold AI’ analysis points to messages from the technology industry that eye-sci-fi does not engage with (20). In light of this, Noessel recommends that science fiction creatives could help us better understand real-world AI by telling stories and accurately covering the realities of AI in popular media.

Better Images of AI

To counter the limitations of traditional stock AI imagery the Better Images of AI was set up by We and AI – a non-profit organisation dedicated to improving critical AI literacy among the public. Better Images of AI hosts an alternative stock image library featuring over 100 visuals that challenge common AI tropes and encourage more accurate and inclusive representations.

We’ve collaborated with individual artists, educational institutions, and organisations – for example, Kingston School of Art, AIxDESIGN, Cambridge Diversity Fund, The Bigger Picture and AI4Media. All images in the library are available for free under a Creative Commons license, offering a valuable resource for journalists, policymakers, and researchers looking for more helpful and diverse representations of AI.

Some of the criteria for ‘better’ images of AI include:

- Realism: representing AI as it exists today, rather than relying on speculative visions.

- Diversity: showcasing AI in ways that include a broad range of human experiences and identities.

- Honesty: showing what the AI system can actually do, and nothing more.

Although science fiction/eye-sci-fi images are often excluded from the Better Images of AI library because they focus on speculative futures, there is still room for science fiction-inspired visuals of AI that break free from harmful tropes. By challenging dominant narratives, thinking carefully about diversity, and expanding our imagination, better images of AI from science fiction can shape how we think about AI that is not limited to glowing brains and anthropomorphic robots.

The flipbook

Better Images of AI and the Digital Constitutionalist (DigiCon) recently created a flip book which features a curated selection of artist-created images from the Better Images of AI library. The idea was to bring together visual and critical approaches to artificial intelligence. DigiCon’s science fiction section does not rely solely on conventional eye-sci-fi narratives. Instead, it approaches science fiction as a field for thought experiments, a diagnostic lens, and a tool for regulatory learning. This flipbook was born out of a shared interest between Better Images of AI and DigiCon to show how the two platforms can complement, challenge and learn from each other.

While Better Images of AI provides visuals, DigiCon offers a conceptual framework, inviting readers to think more carefully about AI through embracing the critical perspective and power of science fiction. Although the curated images are not science fiction-based, they open up thought patterns that resonate with the genre and inspire more thoughtful representations of AI, which acknowledge its material reality, expose its current limitations, and explore its actual functions in everyday life.

Sifting through the flipbook, you’ll find some “better images of AI” as well as some personal reflections from the volunteers that are part of the Better Images of AI community, who keep the library going. Their thoughts show how each of the images in the library tell and inspire more thoughtful and pluralistic stories about AI than those which are commonly presented in the dominant media.

Science fiction (and its derivative eye-sci-fi genre) will continue to influence how we think about AI, but if we want more productive and meaningful discussions about its development, we need richer, more diverse visual languages. We hope that this flip book can serve as an inspiration for more productive avenues of framing AI that foster better visuals and narratives around what the technology is and what it should become.

Reference List

- Li L, ‘Diegetic Prototypes in the Design Fiction Film Her: A Posthumanist Interpretation’ (Journal of Future Studies, 2023) < https://jfsdigital.org/articles-and-essays/2023-2/diegetic-prototypes-in-the-design-fiction-film-her-a-posthumanist-interpretation/> accessed 15 July 2025.

- The eye-sci-fi abbreviation was coined by Isaac Asimov in his essay on “The Boom in Science Fiction” in 1981, Asimov on Science Fiction. Asimov used this term to separate the science fiction adaptations in motion pictures from the literary and printed works of science fiction, which he refers to as “s.f.”.

- Better Images of AI, < https://betterimagesofai.org/> accessed 15 July 2025.

- Brennan E, ‘Why Does Film and Television Sci-Fi Tend to Portray Machines as Being Human?’ (Communicating with Machines, Japan, 2016) < https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschmedcon/43/#:~:text=Science%20fiction%20does%20not%20just,understand%20and%20interact%20with%20them. > accessed 15 July 2025.

- Doker Y, ‘#3 The Chicken-Egg Dilemma: Does Sci-Fi Predict or Create the Future?’ (The Digital Constitutionalist) < https://digi-con.org/the-chicken-egg-dilemma-does-sci-fi-predict-or-create-the-future/> accessed 15 July 2025.

- Law H, ‘Computer vision: AI imaginaries and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’ (2024) 4 AI and Ethics < https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43681-023-00389-z> accessed 15 July 2025.

- The Encyclopaedia of Science Fiction, ‘Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’ < https://sf-encyclopedia.com/entry/tsiolkovsky_konstantin> accessed 15 July 2025.

- It is also worth recalling that the very term robot derives from the Czech word robota, meaning forced labour or servitude. Asimov noted that in translating Čapek’s play into English, the term “robot” was chosen over “slave” to mark a distinction between natural and artificial beings. Yet the historical association with subjugation lingers in today’s portrayals, reinforcing fears of rebellion and control.

- Asimov I, Asimov on Science Fiction(Doubleday 1981).

- Davidson H, ‘’Flat and shallow’: Netflix’s 3 Body Problem divides viewers in China’ (The Guardian, March 2024) < https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/mar/22/netflix-3-body-problem-divides-viewers-china> accessed 15 July 2025.

- McMillan M, ‘Netflix’s “3 Body Problem”: Expenscheap’ (The Digital Constitutionalist) < https://digi-con.org/netflixs-3-body-problem-expenscheap/> accessed 15 July 2025.

- Cave A, Dihal K, Dillon S, ‘Introduction: Imagining AI’ in Stephen Cave, Kanta Dihal and Sarah Dillon (eds) AI Narratives: A History of Imaginative Thinking about Intelligent Machines (Oxford University Press 2020)

- Cave S, Dihal K, Drage E and McInerney K, ‘Who makes AI? Gender and portrayals of AI scientists in popular film, 1920-2020’ (2023) 32 Public Understanding of Science 6.

- Even Metropolis was reshaped by early Hollywood’s eye-sci-fi priorities. To make it more marketable, American distributors cut the runtime, simplified the narrative, and removed all mention of Hel, partly because the name sounded too much like “Hell.” Lang later called this edit a cruel mutilation of his film.

- Aeon, ‘AI’s first philosopher’ < https://aeon.co/essays/why-we-should-remember-alan-turing-as-a-philosopher> accessed 15 July 2025.

- Solomonoff G, ‘The Meeting of the Minds that Launched AI’ (org, 6 May 2023) < https://spectrum.ieee.org/dartmouth-ai-workshop> accessed 15 July 2025.

- Innovate Forge, ‘Understanding ANI, AGI, and ASI in Artificial Intelligence’ (Medium, 23 November 2023) < https://medium.com/@InnovateForge/understanding-ani-agi-and-asi-in-artificial-intelligence-6265d01091a1> accessed 15 July 2025.

- Goertzel B, ‘From Narrow AI to AGI via Narrow AGI?’ (Medium, 31 July 2019) < https://medium.com/singularitynet/from-narrow-ai-to-agi-via-narrow-agi-9618e6ccf2ce> accessed 15 July 2025.

- Dihal K and Duarte T, ‘A Guide for Users and Creators’ (The Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence and We and AI, 2023) < https://blog.betterimagesofai.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Better-Images-of-AI-Guide-Feb-23.pdf> accessed 15 July 2025.

- Noessel C, ‘Untold AI’ (Sci-Fi Interfaces, July 2018) < https://scifiinterfaces.com/2018/07/10/untold-ai-poster/ > accessed 15 July 2025.

Visual: https://betterimagesofai.org/images?artist=AlanWarburton&title=VirtualHuman

Attribution: Alan Warburton / Better Images of AI / CCBY-4 / Image by BBC